The gale rocks the scaffolding beneath you. The sweat on your hands causes you to lose your grip on the iron rail. You came up to straighten the boards. Your heart pounds. One foot forward at a time. You can do this. TITANIC needs you. Her iron hull rises beside you. The next brutal gust rocks the narrow platform so much, you cannot take another step. Stranded eighty feet above the ground, you panic.

“Hold on,” someone shouts beneath you. “I’m coming up.”

You focus on breathing. The boards have shifted. You’re too terrified to try climbing down. You sit and wait until a cheerful face appears over the edge. “Hello, Archie,” your pal Thomas Andrews says with his usual grin. “Got yourself in a bind?”

You manage a nervous chuckle. Andrews helps you climb down before he secures the boards himself.

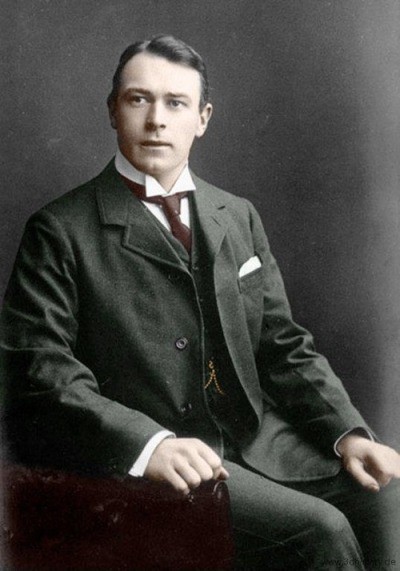

I admire many historical figures, but none warms my heart like Thomas Andrews. I wrote him into my novel The Secret in Belfast with delight but also sorrow (knowing he could not live to the end), but as fond as I am of “my” fictional Thomas Andrews, the real man is even more remarkable (if a little less supernaturally gifted!).

As a writer, it’s easy for me to imagine spending years of my life designing something as beautiful as TITANIC, attending to her millions of details, watching her progress from a keel to the magnificent ship that left Belfast, and then realizing in less than four hours she’ll be at the bottom of the Atlantic. Like many other brave souls that night, her designer, Thomas Andrews, did his best to help those he could. He died with honor, last seen in the Smoking Room contemplating meeting his maker. Maybe he wanted to spend his last moments on earth alone in the heart of his masterpiece, surrounded by exquisite stained glass.

Titanic was one of three sister ships developed by the White Star Line for the transatlantic crossing (from Europe to New York harbor). The others were Olympic and Britannic. The ships carried millionaires in First Class (the price of a parlor suite, the most luxurious the ship offered, was $4,350, or $150,000 today; a regular cabin was $150, or $5,200 today). The middle class could afford Second ($60 then, $2,100 now). And foreigners who wanted to build a new life in America made up Third or Steerage ($15-$40 then, $520-$1,400 today).

Titanic had more passengers on her maiden voyage because of a massive coal strike. In began in late February and ended in April all across Great Britain, when over a million coal miners organized to demand minimum wage rather than the complicated sliding pay scales. They wanted predictable fair pay, especially for dangerous work. The strike crippled coal production, which caused many shipping lines to cancel or delay sailings, or combine passengers from multiple ships onto the few who could afford to sail. White Star diverted coal from its other ships to ensure Titanic would meet her launch date, and all the smaller ocean liners transferred their passengers to her.

Thomas Andrews was a good-natured Irishman with a kind heart. As a young man, he and his friends were jumping on a brass bedstead in a hotel room and broke it. The hotel demanded he purchase it from them, so he took it apart and shipped it to the needy, sick husband of a hotel employee. That should tell you the nature of his character, both mischievous and generous.

Harland & Wolff, the most advanced shipyard in the world, built luxury ocean liners and employed 15-20,000 employees (shipwrights, riveters, welders, engineers, draftsmen, painters, electricians, laborers, and clerks). It served as the beating heart of Belfast’s economy, as one-third of the working class served in the shipyards, and boosted the economy in its demand for iron works, steel production, timber, and textile trades. Thomas Andrews’ uncle on his mother’s side served as the Chairman of the company, Lord Pirrie. (Unfortunately, like many industries did thanks to the sectarian divisions in Northern Ireland, the company had a strictly Protestant hiring policy for many years.)

The ambitious, perfectionist Thomas started working in the shipyards at age sixteen, and worked his way up through every department, until he became the Chief Designer and head of the drafting department. This not only made him well known and liked in the company, but let him understand every facet of the labor, construction, and design of ships. He knew how it all worked, and he had been part of the labor force. His compassion toward workers is shown in the minute details of Titanic, such as the water fountain in the firemen’s quarters, at the top of the spiral staircase. Andrews was, in many respects, fearless; once, when a hot rivet nearly hit him on the head, he kicked it aside, laughed, and went on about his day.

Like any shipyard, the building process of Titanic had occasional mishaps and accidents. In one instance, an associate and friend of Andrews’ called Anthony Frost climbed 80 feet of scaffolding to secure some loose boards. Once up there, Frost became terrified and incapable of climbing back down, so Thomas went up to rescue him before securing the boards himself. (Tragically, Frost and Andrews both went down with the ship.) His kinship to the men of the yard was so great, not only did he refer to them as his “pals,” but all deeply mourned his death.

In 1909, Thomas Andrews married Helen Reilly Barbour, the daughter of a wealthy linen manufacturer and a major figure in Northern Irish industry and politics. It’s likely he met Helen at the First Presbyterian Church in Comber, since she came from a well-respected Presbyterian family similar to his own. His Presbyterian faith encouraged sobriety, service to others, personal integrity, devotion to duty, and courage, all of which he lived out in his private life. They had one daughter.

Andrews made a practice of accompanying his ships on their maiden voyage, to observe any issues in its design in real time and make a note of any necessary improvements. He sailed on Titanic’s sister ship Olympic in 1911 and used his notes from it to improve Titanic before she set sail. When she left Belfast, Andrews boarded her as part of Harland & Wolff’s Guarantee Group, men chosen to help the crew adapt to the larger vessel and notice any flaws in her design. The ship went full steam ahead and diverted its course because of ice warnings. Late Sunday night on April 14, the lookouts spotted an iceberg in their path. First Officer Murdoch ordered them to steer around it, but reversing an engine of Titanic’s size in time to avoid a collision proved difficult. The iceberg tore a five-hundred-foot gash in her side.

Andrews and his co-designer, Alexander Carlisle, had designed all three ships to stay afloat with any four compartments flooded. Only a short time earlier, the Olympic had proven this technique as effective in a collision with the admiralty vessel, the HMS Hawke. The former ship suffered minor damage, but the latter had expensive damage to her bow (designed for warfare ramming of other ships). With five compartments punctured, water filled Titanic, pulling her down by the prow. Andrews did all he could to help load the lifeboats and get the women and children to safety, knowing half the passengers would die. They did not have enough lifeboats to save them all. Trade regulations at the time stipulated a certain number. They had set these regulations decades earlier for smaller vessels and did not update it as ocean liners grew in size. Andrews had designed the lifeboat davits to take another row of boats inside them, enough to accommodate all the passengers, but the White Star Line refused. No one else carried an extensive number of lifeboats; why should they?

Though aware of such minor details as the wrong choice of paint color or too many screws in the stateroom hat racks, Andrews felt satisfied with Titanic, and remarked on April 14 that “she is as nearly perfect as human brains can make her.” Yet, that very night he was forced to assess the damage, encourage passengers to put on their lifebelts, make certain the staterooms were evacuated and assist women into the lifeboats. It’s hard to imagine what went through his mind as he grappled with the reality of their situation, his guilt over his ship being inadequate, his anger at too-few lifeboats, and wrestled with his own mortality and the certainty of his death. Many said he seemed calm and prayerful at the end of his life. That he urged others to pray and reminded them to trust in the Lord.

The maritime disaster killed 1,500 people, including Andrews and his entire Guarantee Group, the larger portion of the crew, one of the most respected captains in the industry (on his retirement voyage), many prominent businessmen, and hundreds of steerage passengers. But Titanic was a monumental advancement in ship-building. She sank evenly, allowing the crew time to launch all the lifeboats and one collapsible. Had they had enough lifeboats for all passengers, this would have seen them all away from the ship before she sank. The poorer design of modern cruise ships now means many of them tilt onto their side, rendering half their lifeboats inaccessible.

Some questioned the quality of the steel, but as the Olympic proved in her collision, it had no flaws. After being refitted and updated to reflect what they learned from Titanic, she survived another collision. While transporting U.S. troops on their way to France in 1918, she rammed a German submarine. She returned to Southampton for repairs with two hull plates dented and her prow twisted to one side, but not breached. (Later, they learned the submarine had been planning to torpedo her.) For her war efforts, she earned the name “Old Reliable.” Many celebrities traveled on her in the 1920s, including Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford, Cary Grant, Douglas Fairbanks, and Prince Edward, the Prince of Wales.

The third ship, Britannic, struck a mine and sank in 1916. Olympic remained in service until 1935. By the time of her retirement, she had completed 257 round trips across the Atlantic, transporting 430,000 passengers on her commercial voyages, and traveled 1.8 million miles. You can still find pieces of her paneling, furniture, fireplaces, and her clock in hotels in England.

Belfast mourned Thomas Andrews deeply, as a person of integrity. Many newspapers honored him for his heroism. Helen never married, but devoted her life to charitable work. At the end of his life, Thomas Andrews died as he lived, with grace, honor, and dignity.

Want more than just the tragedy of the Titanic? Dive into a tale of myth, mystery, and the men who built her in my novel, The Secret in Belfast.