In May 1517, there was a large contingent of French and Italian immigrants in London. They lived near the city’s financial district and provided many services for the court. They were of such a number that male Londoners had trouble getting positions or finding honest work and started resenting the court’s “preference” for “foreigners.” This stirred up old resentments against the French, and “politicking” individuals with strong anti-foreigner biases took advantage of; they blamed the French and Italian immigrants for stealing jobs from the English, and suggested the “sweating sickness,” an unknown recurring lethal plague in the period, originated with the foreigners.

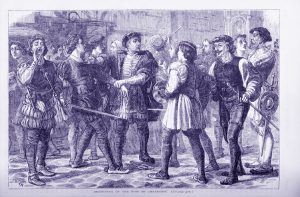

In the weeks leading up to May Day, assaults and crimes against foreigners broke out in the city, with escalating levels of violence. Cardinal Wolsey, who ran England for the fun-loving King Henry, got wind of planned violence on the holiday and suggested a curfew. Bonfires and late-night celebrations fell on May Day; as they enforced the curfew, resentment turned into resistance that became a mob that surged through London, heading for the financial district. Thomas More briefly halted the mob as the under-sheriff of London, but his attempts to calm them down and send them home were thwarted by the Europeans in the surrounding houses throwing stones from the upper windows and shouting insults. The mob pushed past More and laid waste to the district, breaking down doors, throwing wares and furniture into the street, and stealing whatever they could find. One of Henry’s (foreign) secretaries barely escaped with his life.

Once made aware of the situation, Henry VIII ordered martial law imposed in London; by the time his soldiers arrived at dawn, the mob had dissipated, but 400 rioters were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower, many of them only fourteen years old. Because of the potential political ramifications of foreigners not feeling safe in London, and the effect it might have on foreign trade, their actions were judged as high treason with the penalty of death. The men responsible for preaching violence were quickly, publicly, and brutally executed, but Cardinal Wolsey and the king’s wife, Catherine of Aragon, got pardons for the rest in a dramatic public appeal before King Henry.

It is likely Henry never intended to execute the 400 young rioters, but by making an example of a few, the public viewed his pardon of them at the behest of his tearful Spanish wife as an act of great mercy. It won him back the loyalty of London, shaken through the court’s perceived favoritism of immigrants in a severe economic downturn. In searching for a scapegoat, rioters found it easier to point fingers at foreigners than to deal with the deeper social problems of the period. Class warfare, political sleight of hand, and shifting the blame was common in London, with the added misfortune of no middle class. You were rich and a nobleman, or poor and a working man. Some nobles were without lands and incomes from estates; but the wages of a working man were so low and the education and required income of the nobleman so high, the employer could not afford the nobleman and the nobleman could not live on the wages of his employer, so there was no chance of an honest man earning an honest wage, nor of a poor man bettering his education in the hope of a greater one.

Thomas More pondered in his book Utopia whether a society without a middle class, with encouraged poverty and social unrest, and a government so corrupt and complex in its laws that it turns honest men dishonest, is amoral. He wondered if we first “make thieves and then punish them.” Perhaps that question is as relevant today as it was in the days of yore.

Thomas More pondered in his book Utopia whether a society without a middle class, with encouraged poverty and social unrest, and a government so corrupt and complex in its laws that it turns honest men dishonest, is amoral. He wondered if we first “make thieves and then punish them.” Perhaps that question is as relevant today as it was in the days of yore.

Thomas More pondered in his book Utopia whether a society without a middle class, with encouraged poverty and social unrest, and a government so corrupt and complex in its laws that it turns honest men dishonest, is amoral. He wondered if we first “make thieves and then punish them.” Perhaps that question is as relevant today as it was in the days of yore.

Intrigued by the politics and passions behind the Tudor dynasty? Explore the hidden truths of the early Tudors in my historical fiction series, The Tudor Throne.